Introduction

Museum digitation takes existing physical objects held in museums and creates a digital backup. This can be performed in many ways, the most common being digital photography. Collecting 2D digital images of the collections allows for online viewing by researchers and the general public and improves the shareability of the archive. This is commonly applied to objects such as plants, insects, books, and artwork (Figure 1), capturing the structure of the object in a single plane. This is a suitable approach for preserving colour and detail when digitising artwork, manuscript pages, skin, and fur patterns.

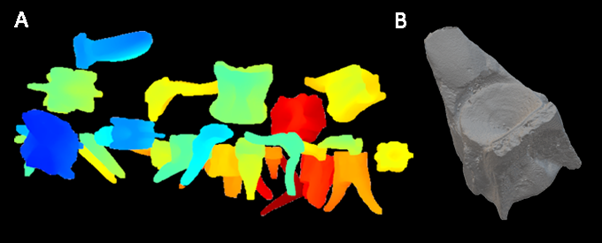

More recently, photogrammetry has been adopted by museums to capture the shape of objects that are less amenable to 2D photography. Photogrammetry uses multiple digital photos collected from varying positions around the object to reconstruct its 3D shape (Figure 2). However, the process of photogrammetry is considerably more time-consuming, both in terms of initial photography and downstream post-processing. It is also limited to capturing surface details, and cannot capture internal structural details or areas of self-occlusion where the camera cannot be angled.

But what lies beneath? How do ceramic pots, animal skulls, or ancient statues appear internally? Much insight into the creation and evolution of these objects can be determined by retrieving the subsurface 3D structure of the objects. To capture internal details, computed tomography (CT) imaging can be used. In non-medical CT, the object is rotated 360 degrees whilst thousands of 2D x-ray projections are collected. From this, a reconstruction of both the external and internal surfaces can be generated. 3D internal information can provide information on the manufacturing process, highlight potential forgeries, or assist museum preparators and curators in preserving objects.

The CT digitisation process is complex; single objects can be scanned at extremely high resolutions, yet at considerable financial and time cost. To begin to resolve this, we organised the first of a series of workshops with key stakeholders from universities, museums, and CT facilities. These workshops aim to assess the digitisation problem, explore possible avenues of research, and ensure the final pathway is both sustainable for all fields and records as much valuable information as possible.

Day plan

The workshop was planned as a half-day event due to participants travelling considerable distances. After introductions, acknowledgements were made to the Software Sustainability Institute (SSI) for funding the workshop, and the National X-Ray Computed Tomography (NXCT) centre for hosting. The format consisted of two keynote speakers in the field of museum digitisation (Dr Charlotte Brassey and Dr Connah Kendrick, MMU), followed by a CT facilities tour and a roundtable discussion with participants to conclude.

The roundtable discussion considered the features of museum digitisations most urgently needed to progress the field forward, such as: • Understanding digitisation goals • Target collections • Infrastructure challenges • Desired outputs (software)

NXCT cntre

To facilitate this, Dr Tim Burnett of NXCT centre (University of Manchester) kindly provided a tour of their facilities to the group. He highlighted recent advances in phase-contrast analysis and ‘colour’ microCT scanning made at the facility, in addition to providing an overview of the suite of machines available to researchers for potential mass digitisation projects.

Outcomes

During open talks, users’ diverse motivations for digitisation using CT scanners were discussed in detail. The relative merits of 3D digitisation via photogrammetry vs lab-based CT were considered. In most cases, CT was desired as the gold standard, but there were some limitations associated with facilities access and cost. In many instances, digitisation goals were primarily research-based, with a specific project in mind and often limited funding. The main issue highlighted was the sheer diversity of objects that require digitisation and how an object’s shape, size, weight, and fragility affect its ability to be scanned. Some collections posed unique digitisation challenges, either due to objects being too large for conventional lab-based CT imaging or some being too small for conventional photogrammetry. The nature of some object’s preservation poses additional difficulties, such as those submerged in liquids (causing distortion) or insect collections with metal pins mounted through them. The pins can cause issues with both photogrammetry and microCT, meaning the sample cannot be manually separated. The facilities cost involved was a significant limitation to microCT scanning, preventing its widespread adoption. This challenge increases when factoring in sample transport and data storage costs. Attendees expressed a desire to increase object throughput as a means of improving the cost-effectiveness of CT scanning, via the digitisation of multiple samples within a single scan and/or batch scanning of samples out-of-hours. Attendees attested to performing ad-hoc mounting of their collections by creating bespoke holders to capture multiple items in a single scan. However, many of these mounts need removing via post-processing of the scan and are not transferable to a subsequent scan project. The final deliverables of the digitisation process were discussed in detail; everyone shared a common interest in getting the results in a quickly accessed format. Users highlighted the incorporation of specimen IDs from external databases as being particularly essential, especially when capturing a large number of objects (100s-1000s) per scan. This is particularly a priority when capturing objects of outwardly similar morphology, such as collections of coins, teeth, or bone fragments, in which losing track of object IDs may render the item meaningless. There was also a strong preference for having the outputs accessible to software downstream for future processing and analysis. This includes making any software compatible with currently widespread applications in the forms of plug-ins rather than new standalone software. This would help ensure the software is easily used by a broad audience and requires less institutional oversight. Lastly, we discussed current bottlenecks in attendees’ workflow, to identify where the software should first be targeted to increase immediate throughput. Ease of use and the creation of a standardised workflow in open-source technologies were flagged as priorities. Currently, the available technologies require considerably training to begin the process, and specific add-ons to complete the task. Additionally, current workflows contain steps vulnerable to human error which should be resolved.

Next workshop

The next workshop will be announced via the website

Website

I am also happy to announce the website for museum digitisation is now available online: museum3d.github.io This hub will act as a central repository for information on the organised workshops and our ongoing research into museum digitisation.

Conclusion

The day highlighted the diversity of research taking place in-and-around the sphere of museum digitisation. For any software to assist in this process, it will need to be highly dynamic and capable of working across many different formats and samples. The desire for high-throughput data collection from CT scanners is high. However, future software must be compatible with flexible mounting. regimes and be capable of separating multiple samples within a scan volume. Maintaining object identities throughout was considered essential. Participants recognised an inevitable trade-off between scan quality and throughput. Many favoured slightly lower-quality scans in order to digitise a greater proportion of a collection. Having integrated technologies can aid the process of museum digitisation by allowing researchers and curators to process many samples simultaneously, and by providing diverse solutions to both sample mounting and downstream data processing. Continued dialogue between academics, curators and facilities staff is essential to ensure valuable user-led software is developed. The next workshop will focus more specifically on software functionality, and existing in-house software will begin to be modified in response to feedback from the initial workshop.